In this short reflection, Dr. Sandra Styres and Dr. Huia Tomlins-Jahnke discuss the decision process in choosing the cover image for Indigenous Education: New Directions in Theory and Practice, which they co-edited with Spencer Lilley and Dawn Zinga.

Senator Murray Sinclair, former Commissioner for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in Canada, said it best when he stated that “Education got us into this mess and education will get us out” and further that “education is the key to reconciliation.” In the mid-1990s approximately 86,000 residential school survivors brought the largest class action lawsuit in Canadian history against the Canadian government. The lawsuit resulted in a settlement agreement and one of the conditions of that agreement was the establishment of the TRC (TRC, 2012). Residential schools were absolutely spaces of contestation and violence—they were also spaces of Indigenous resistance, resiliency, and survivance (Haig-Brown, 1988). Residential schools are one of the long-lasting and far-reaching symbols of colonial education and contestation in Canada.

What is important to note is that current ways of thinking about and doing education along with the Canadian reconciliation “project” remain mired in colonial discourses. These colonial discourses mean that education continues to happen in spaces of contestation. In general terms, contestation occurs in the shared spaces where disparate worldviews collide. In educational contexts where education is provided through mainstream curriculum that does not include or value Indigenous perspectives, contested spaces are constantly triggered, engaged, enacted, and maintained to the detriment of Indigenous learners and educators. Therefore colonial-centric education has long been a site of colonial violence and contestation for any colonized Indigenous people no matter where they reside. The purpose of our book was to open up dialogue so that the various forms of contestation across diverse educational contexts can be acknowledged and engaged. Each author represented in the book joined together to bring these contested spaces into view. Education is seen to be critical to issues relating to sovereignty, governance, and self-determination for Indigenous peoples and one that can have a profound influence on Indigenous-settler colonial relations.

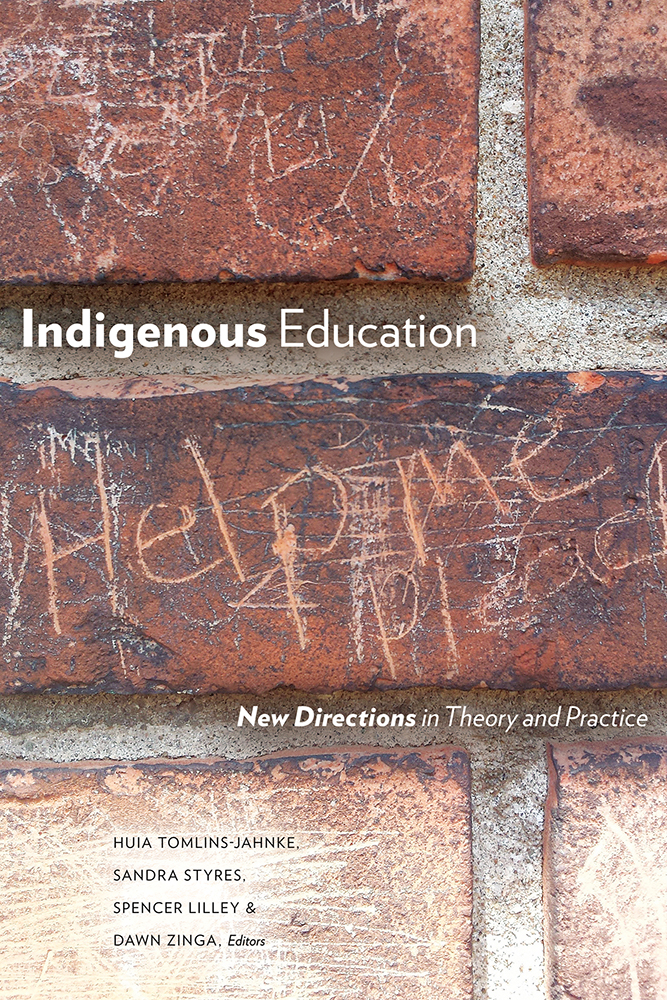

That said, one of the most important decisions we had to make was what imagery we would put on the cover of the book that would encompass all of these diverse perspectives related to education as a primary site of contestation, continued violence, and active resistance for Indigenous peoples. Upon very careful and respectful consideration it was decided to use an image of a portion of an exterior wall of the Mohawk Institute, a former residential school that operated in Ontario, Canada from 1828 to 1970 (142 years). Upon extensive community consultation, survivors of the Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School decided that it should be restored and preserved to stand as a testament to the colonial violence that occurred in residential schools across Canada and to ensure that the physical evidence of this dark chapter in Canadian history is never forgotten.

Sandra consulted with community Elder Tae ho węhs (Amos Key, Jr.)1 who stated that it is the survivors themselves who are leading the proposal and fundraising for a memorial park that will be located at the site of the Mohawk Institute. Further, that the Mohawk Institute will stand as Canada’s first “Canadian Museum of Conscience.” The Mohawk Institute itself is scheduled to re-open as a museum in 2020.

Elder Tae ho węhs has also said that he supports the use of the image of a portion of an exterior wall of the Mohawk Institute for the book cover. The photograph was taken by Huia Tomlins-Jahnke, Mäori scholar and one of the co-editors of the book. It was her first visit to the Six Nations community and to a residential school in Canada. To us, the image represents the ways we are immersed in and engaging within spaces of contestation that, for many, are triggering and traumatizing spaces that continue to perpetuate harm for Indigenous peoples.

Sandra has, on many occasions, stated that in order to clearly envision where we need to go, we need to look back to where we have been, to understand how we got to be here / now / in this place at this time. We, along with our fellow co-editors, realized that the image was left as a gift to us—in this time and in the future—from the children who attended the school in the past. Following Indigenous ethics of relationality and recognizing the profoundness of the gift, in a gesture of reciprocity and in adherence to local protocols, Sandra went back to the school and offered sacred tobacco as a thank you offering to the spirits of the children who attended the school for their gift.

Dr. Sandra Styres is of Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk), English, and French descent and resides on Six Nations of the Grand River Territory. Sandra is a Canada Research Chair in Iethi’nihsténha Ohwentsia’kékha (Land), Resurgence, Reconciliation and the Politics of Education as well as an Assistant Professor with the Department of Curriculum, Teaching and Learning at OISE, University of Toronto. She is also Chair of the Dean’s Advisory Council on Indigenous Education, and Co-Chair of the Deepening Knowledge Project. Dr. Styres’ research interests specifically focus on: Land-centered education; Indigenous resurgence; politics of decolonizing reconciliation in education, higher learning contexts; integration of Indigenous perspectives into teacher education programming; pre-service and in-service teacher development; Indigenous philosophies and knowledges; culturally aligned methodologies and theoretical approaches to Indigenous research; ethics and protocols that guide the work in Indigenous and non-Indigenous research collaborations and community engagement.

Dr. Huia Tomlins-Jahnke (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Toa Rangātira, Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Hine) is a Professor of Māori and Indigenous Education at Massey University. She is also the Director of the Te Mata o Te Tau Academy for Māori Research and Scholarship and the inaugural Toi Wānanga Fellow. Huia coordinates two kaupapa Māori immersion initial teacher education programs that prepare graduates for teaching in the kura kaupapa Māori system of education. Her research interests include Māori and Indigenous development, Indigenous research methodologies, the ethics of knowledge production, and Māori education.

References:

Haig-Brown, C. (1988). Resistance

and Renewal: Surviving the Indian Residential School. Vancouver, BC: Arsenal

Pulp Press.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2012). Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada: Interim report. Retrieved from: https://www.falconers.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/TRC-Interim-Report.pdf

Notes:

1 Tae ho węhs is a Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) Faith Keeper at Six Nations of Grand River Territory. He is a decolonizing educator and social justice advocate for First Peoples’ human, civil, and linguistic rights. Tae ho węhs is Director of First Nations Languages at Woodland Centre, a Professor at University of Toronto’s Centre for Indigenous Studies, and most recently Vice-Provost, Indigenous at Brock University.