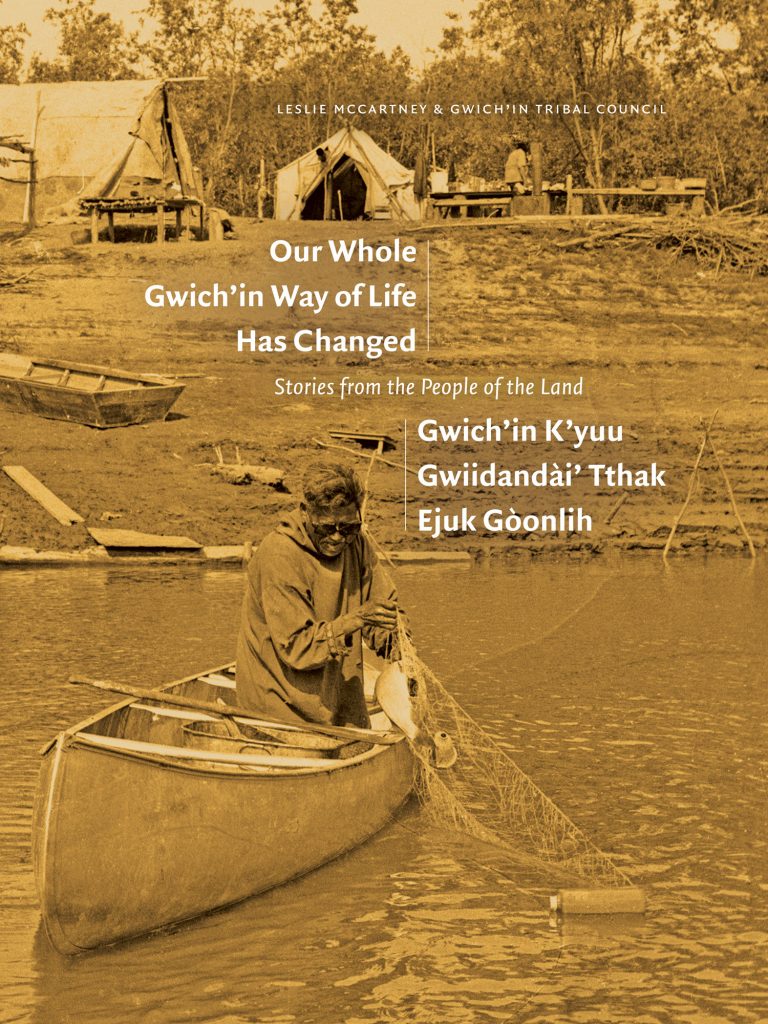

Guest post by Stephen Ullstrom, indexer for Our Whole Gwich’in Way of Life Has Changed / Gwich’in K’yuu Gwiidandài’ Tthak Ejuk Gòonlih.

There is a welcomed and long overdue movement within Canadian publishing to publish more Indigenous works and to better acknowledge and collaborate with Indigenous authors, communities, and editors within the publishing process. I saw this firsthand at The Writing Stick: Sharing Indigenous Stories conference in 2017, hosted by the University of Alberta Press, and it has been an honour to write the index for Our Whole Gwich’in Way of Life Has Changed / Gwich’in K’yuu Gwiidandài’ Tthak Ejuk Gòonlih: Stories from the People of the Land, by Leslie McCartney and the Gwich’in Tribal Council, which so wonderfully embodies the spirit of that conference and this movement. As you read the interviews with the Elders, there is such a strong sense that this book was created by the community to give back to their community, both their history and traditional knowledge and also a sense of who they are today.

Indexing the book was an intimidating process. I had an immediate inkling of that when Duncan Turner, the production editor, suggested I might want to bring someone else on, when he first proposed the project to me. Duncan was right. I did hire two subcontractors, Margaret de Boer and Jess Klaassen-Wright, to help me create the rough draft. While thankful for their help, completing my portion of the rough draft and then editing the full index, for all 800+ pages of the book, was still one of the largest and more challenging projects I have ever done. But the challenge also presented an opportunity to think deeply about how best to shape the index to meet the needs of the audiences, intended and otherwise, who will use it. On Margaret’s suggestion, the idea of doing a workshop on indexing this book, and on indexing oral history and Indigenous texts more generally, came about.

As indexers, we recognize the need to be part of the processes of decolonization and reconciliation within knowledge production, especially as more books by and about Indigenous Peoples are being published and will require indexes. We also recognize that most of us are settlers, and many of us have concerns that we will unintentionally bring and reinforce colonial biases. Unfortunately, I am not aware of any experienced Indigenous indexers.

The Indexing Society of Canada/Société canadienne d’indexation (ISC/SCI) is working to change this through a bursary for underrepresented and/or marginalized groups. For the time being, though, it is the responsibility of existing indexers to combine their expertise with respect, sensitivity, and seeking to listen and understand in order to index Indigenous texts in a way that serves the communities who created this knowledge.

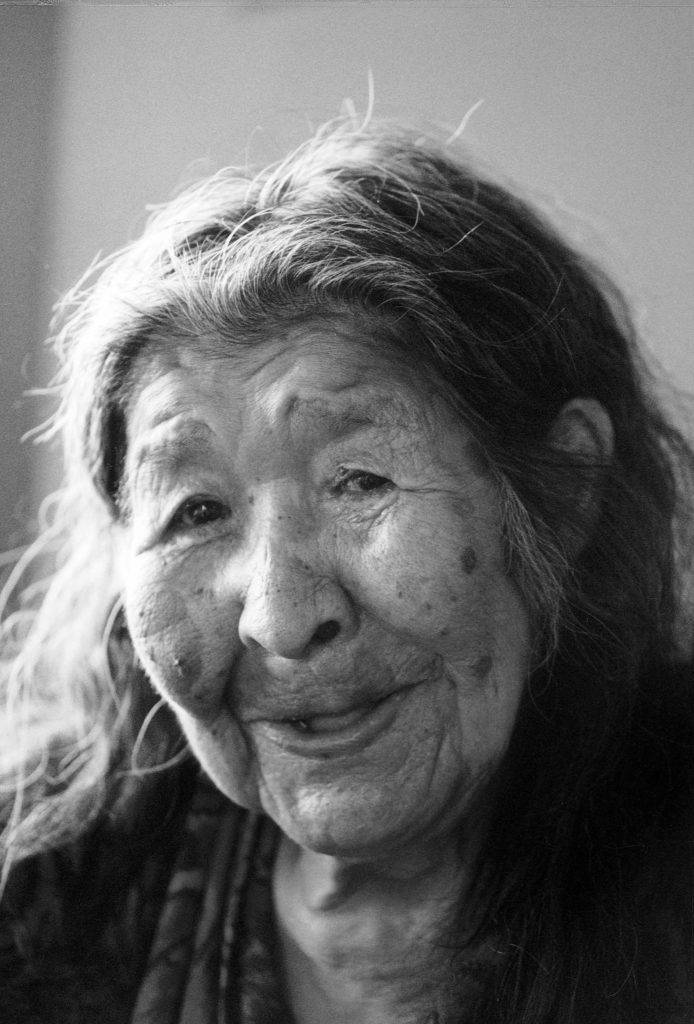

To that end, twenty-nine of us gathered on Zoom on February 20, 2021, from across Canada and the United States, for this workshop. The workshop was hosted by ISC/SCI, and we had twenty-six participants, ranging from brand-new indexers starting their careers to indexers with over a couple decades of experience. Leslie McCartney, author of this book, also joined us and was able to provide insight on oral history and aspects of the book, as did my collaborator, Elim Ng, who used her teaching experience and understanding about power and knowledge production from her doctoral degree to help design the workshop and also serve as co-host. To help focus our discussion, we used the chapters containing the interviews from Annie Benoit and Sarah Ann Gardlund, along with the index.

Annie Benoit

Sarah Ann Gardlund

Some of the takeaways from the workshop include:

- Write the index for the community. In the past, so much of knowledge production has been about Indigenous Peoples for non-Indigenous Peoples, and so part of reconciliation is about creating space for Indigenous communities in the production process. For the index, this means, in part, focusing on the community not only as knowledge creators and keepers but also as a key audience for whom this book was written. Thinking about how the community may use the book can shape decisions about how to structure the index and what entries to include.

- Index what is on the page. Colonizing assumptions can include thinking that Indigenous Peoples only exist in the past, or that the only value from their stories are historical and traditional knowledge, or that the focus should be on traumatic events such as residential schools. While traditional knowledge and residential schools did feature in the interviews, the Elders discussed so much more, including aspects of modern life. Sarah Ann Gardlund, for example, discusses being a CBC radio host, involvement with pipelines, and snowmobiles. As indexers, we need to put aside our own assumptions about what is important and pay close attention to what the authors and Elders want to say.

- Acknowledge both the content and the speaker. In oral history, who said what is often just as important as what was said. This can require double- or triple-posting information under both person and subject entries. The danger, though, is that the number of entries can seem to explode exponentially. View each piece of information from different angles and decide which angles are relevant to include in the index.

- Narratives are not always linear. In oral history, and in some Indigenous storytelling, the narrative thread can circle back to previous topics and it is not always clear when one subject ends and the next begins. Leslie McCartney also highlighted that oral history includes embedded knowledge, which the Elders assume you know, and so the knowledge is not made explicit. While the authors of this book did an excellent job trying to make visible the embedded knowledge, it is still a good reminder, as indexers, to be careful when we read, to accurately pick up all that is being discussed.

- Privilege Indigenous terms. Gwich’in place names featured throughout this book, as well as terms for a few other items, such as berries. Language is a key aspect of culture and identity, as well as a rich source of knowledge, so I wanted to give preeminence to the Gwich’in terms by making them main entries. At the same time, we cannot assume that all users of the index will speak Gwich’in, so it is also important to include the English, either as double-posts or cross-references, so that entries can be found either way.

- Names, names, and more names. Family and genealogy was a recurring theme in all of the chapters, and I got the sense that community members may use this book to better understand their own family histories. I made the decision to include all names in the index, even minor references. With that decision, though, came the challenge of differentiating between identical and similar names; individuals with both modern and premodern names; nicknames; references using a partial name or a family title, like mother or grandfather; and women who may have changed their surnames upon marriage. Pay attention to who is being discussed, how they are referred to, and try to track them across the text.

The workshop lasted two hours. We needed every minute of it.

Sharon Snowshoe, Director, Culture & Heritage of the Gwich’in Tribal Council gives a copy of the community’s new book to Mary M. Firth, the only Elder left of all the Elders who were interviewed for the project.

The Elders’ stories, and oral history generally, are a rich source of knowledge. Yet given its embedded knowledge and semi-structured nature, it can be difficult to quickly locate and retrieve information. A well-written index can make that knowledge more accessible by organizing the contents in a searchable way and by making connections between different parts of the text. Making that knowledge more accessible, and writing the index for the community that produced and owns the knowledge, can also be part of the work of decolonizing knowledge production and of reconciliation.