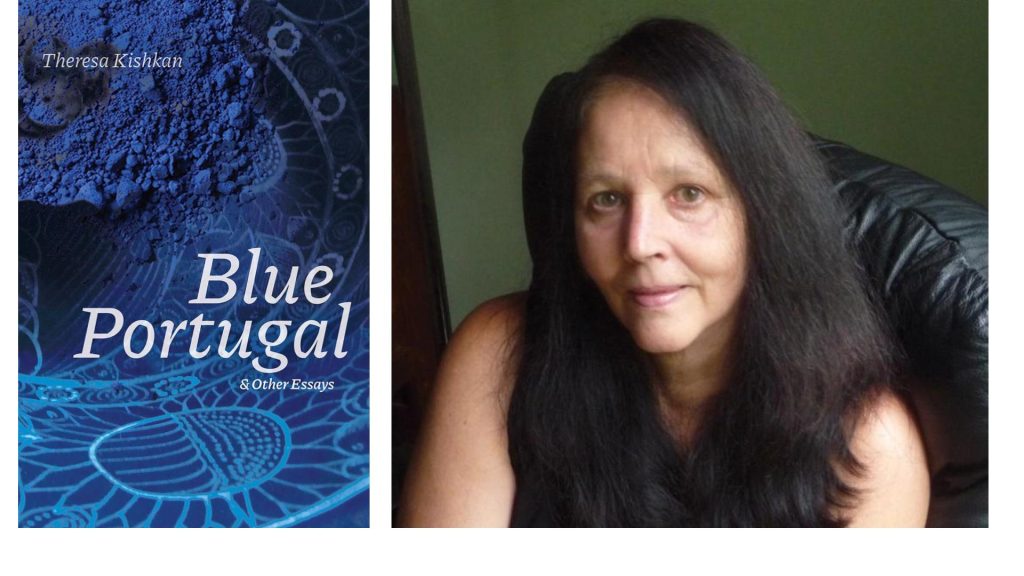

A guest post by Theresa Kishkan, author of Blue Portugal and Other Essays

Many of us grew up learning the essay as a formal container for critical analysis but the form has evolved, in the way a plant might evolve, hybridize in response to new soil conditions, weather, and use requirements. It’s the later possibilities of the essay that interest me most—its generous capacity to hold a writer’s interests in subject matter, as well as moments of poetry, phrases of song, recipes for really good soup, analysis of data, interrogation of known facts, how these can be braided in a simple three-strand arrangement of ideas or themes or a more elaborate confection that allows stray tendrils, and how the writing can use the entire page as a kind of open map, a musical score, or a grammar of pattern language. It’s not that I want to abandon traditional narrative as a mode of expression. In some of the essays in Blue Portugal and Other Essays, narrative is employed to shape a story that interests me, a family story for which I am aware of only fragments of the whole; by attending to the possibilities of the story, how it might be brought to light if I ask questions of it, survey the historical record, and arrange the story’s elements this way and that, superimposing a literal archival map on the liminal spaces of memory, I am often rewarded with a version of the truth.

Some essay collections are unified thematically or chronologically around a writer’s life so that a reader understands the book to be a form of memoir. Blue Portugal and Other Essays does not aspire to memoir exactly. There are connections between the individual essays, yes, there are times when they talk among themselves, refer the reader to others in the group, but my intention was not to create a unified set of texts, with a logical flow. What the essays share is a sensibility—mine, of course, but also I know that I am interested in ideas and terrain which often share something in common. The rivers of my home province echo the venous system of my body. The indigo powder I turn into dye in turn shares a palette with entoptic phenomena. The title essay remembers a wine I first drank in my grandmother’s homeland. These are personal essays after all, not rhetorical or expository ones, so I’m at the heart of each one. Mine is the voice that invites the reader in, welcomes you at the door. My heart is on the sleeve of each essay. I’m the woman on the raft in the Thompson River and in the restaurant in Prague, in the PET tunnel in the B.C. Cancer Centre, portioning out her parents’ ashes on a beach on Vancouver Island, in a kitchen on the Sechelt Peninsula sewing a quilt from indigo linen she’s dyed on a cedar bench by her garden while pileated woodpeckers teach their young to fly nearby.

My essays are mindful of the company they keep. Kathleen Jamie, the late Ellen Meloy, Ian Maleney, Anne Carson, Sinéad Gleeson, Peter Sanger, Lorri Neilsen Glenn, Brian Dillon, Lloyd Ratzlaff, Jane Silcott, Anik See, Rick Bass, and Maggie Nelson, among others: they’ve published celebrated collections of essays that use the form in creative and innovative ways. I read and I listen for how their sentences move across the page, a path forming in their wake. I am there, my own sentences following, joining them briefly, then meandering off the path to take the view from a small rise in a field, edged by a marsh. I tie a thread to a branch to remember my place. There are birds singing—listen! A yellow-head blackbird in the reeds by the water—! A tree hanging its leafy boughs over a slow creek where trout idle and the sky is reflected blue in the clear water. Dragonflies hover. I spread out the small quilt my grandmother made for my brother, patches of her housedresses and my grandfather’s pyjamas. Pause with me, lie on your back in the soft grass. Human thought in real time. Sometimes the mind sleeps and the essay lies quietly beside it, waiting. Sometimes the mind walks tentatively into a cave and runs its fingers along a damp wall, a spiral of ochre dots, a long-horned aurochs, a horse paused in profile. In the far distance, my grandchildren are turning cartwheels, my husband of more than forty years is dreaming of the months he spent planning the rooflines of our house. You are welcome here. Anyone who has followed the thread this far knows what I mean.