A Guest Post by Keely Shirt

The first time I came across the image of my father in the media, I was in the sixth grade. My entire class was seated around one of those classic wheeled TVs. A 20-minute interlude led into a scene outside of a sweat lodge, where young men were speaking on the issue at hand; at the tail end of the scene, a young man in what might be the smallest men’s bathing suit I have ever seen was last to speak. I was somewhere in the middle of realizing who that young man was when my classmates began to point and shout, “Is that your dad?” Yes, that young man in the fluorescent orange Speedo was my dad. Mind you, at this point in my life I was living in my mother’s hometown, Fort Vermilion, population of 600 people, a remote Northern town. More than embarrassment, the feeling of the room was a sort of astonishment, like “Wow, we know someone on TV,” though the contents of the video are vague to me now.

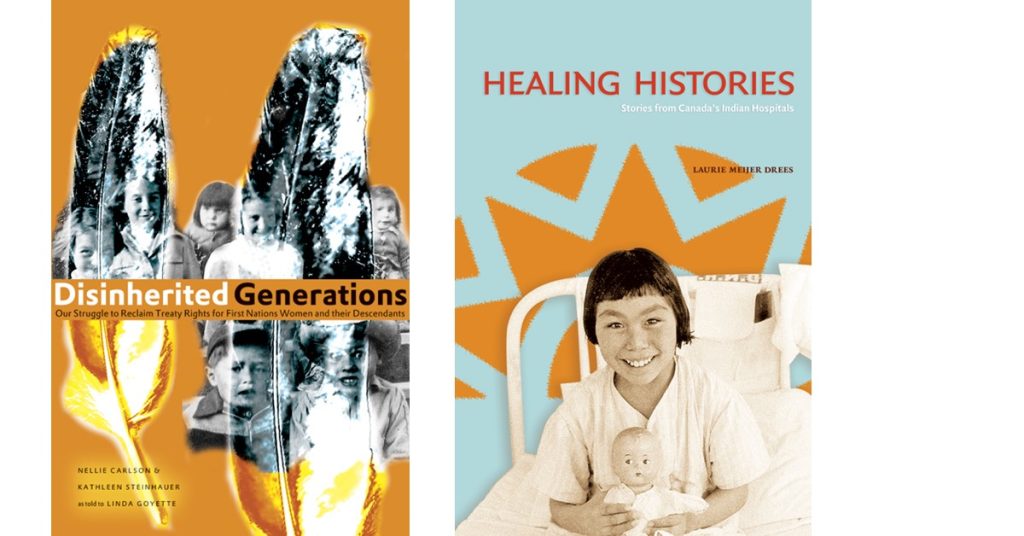

The most recent time was just last month when I was working on a project with the Press’ electronic editions. I was checking some of the chapters in our title Disinherited Generations: Our Struggle to Reclaim Treaty Rights for First Nations Women and their Descendants for accessibility. I chose an image of children, the one featured on the cover, to check the text-to-speech functionality in an accessibility e-reader. Read aloud to me was, “…Some of the Carlson children and a friend, Pat Shirt.” I couldn’t recall seeing my father this young, seeing him as a child, but the longer I looked, the more the child looked like him. I flipped through more pages of names I knew, relations and faces I was familiar with. A photo of my kokum Edna Carlson on her wedding day, with her husband Ralph Shirt. Another image that I had not seen before, another moment with young faces of people I knew.

In another image sits Chief Pakan, my great-great-grandfather. In conversation with my parents, they told me, “You could probably paint a picture of the history of western Canada through your ancestry.”

I can see portions of my history in various titles at University of Alberta Press. For example, Healing Histories: Stories from Canada’s Indian Hospitals features a collection of stories on the history of tuberculosis in Indigenous communities. My mother was sent to hospital for tuberculosis as a child, where she spent eight months alone, confined to a bed. The second time she became sick, at the age of twelve, her mother wrote a letter to the hospital, imploring them to send her the medicine, so my mother would not have to go back to the hospital again. Five out of eight of her siblings went to hospitals across Alberta for tuberculosis treatment. The book contains information about the Charles Camsell Indian Hospital, where my father’s mother and his sister went for treatment.

At the request of my mother, I will add that her time in this hospital included one Christmas morning. Early in the morning, my mom and another girl decided they wanted to look their best for Christmas day. So they snuck into the large room where the pajamas were kept and changed into fresh ones. In their minds, this was one way to make Christmas morning as special as it could be, considering the circumstances. When the nurses found out, for punishment, they strapped my mother and the other young girl into straitjackets and tied the straitjackets to their beds. They lay strapped down for two hours on that Christmas morning. This was not abnormal treatment for children in this hospital, she said.

Working on this large technical accessibility project, I had been so focused on the task at hand that I had not realized I had opened a book that was so personal to me. This serves as a reminder to take time to notice the details that make these works important; to understand and admire them. And, even if I cannot literally find myself in them, to see the reality of it. To remember these histories, rights, and treaty rights, which those before me have struggled for and have maintained, and to ensure the continued reclamation of rights for many Indigenous peoples and our descendants.

And although in this post I have touched only briefly on the contents of these titles, and the importance of reclamation of treaty rights and Indigenous histories, I implore you to learn more.

Note from UAlberta Press: The Book Publishers Association of Alberta partnered with Alberta Municipal Affairs’ Public Library Services Branch to create the Prairie Indigenous eBook Collection, accessible through local libraries, and containing over 200 electronic editions. Of course, Indigenous publishers in Canada continue to lead in publishing key stories and voices.